"When They See Us" and The Importance of Black Humanity on Screen

I was not even born yet when five young Black and Latinx boys from Harlem were all tried and falsely convicted for the rape and attempted murder of Trisha Meili. Meili was attacked while jogging in Central Park in 1989 — the trials of the five boys lasted until late 1990, nine years before my birth. I was not yet a student at Columbia University, roaming the now-gentrified neighborhood the five men once called home.

I am 19 years old today and close in age to Antron McCray, Kevin Richardson, Yusef Salaam, Raymond Santana, and Korey Wise — who have come to be known as the “Central Park Five” — when they were caged. And every day I become more aware of the brutalizing power of the criminal justice system that was awaiting me even before I was born, a criminal justice system that preys on Black boys like myself.

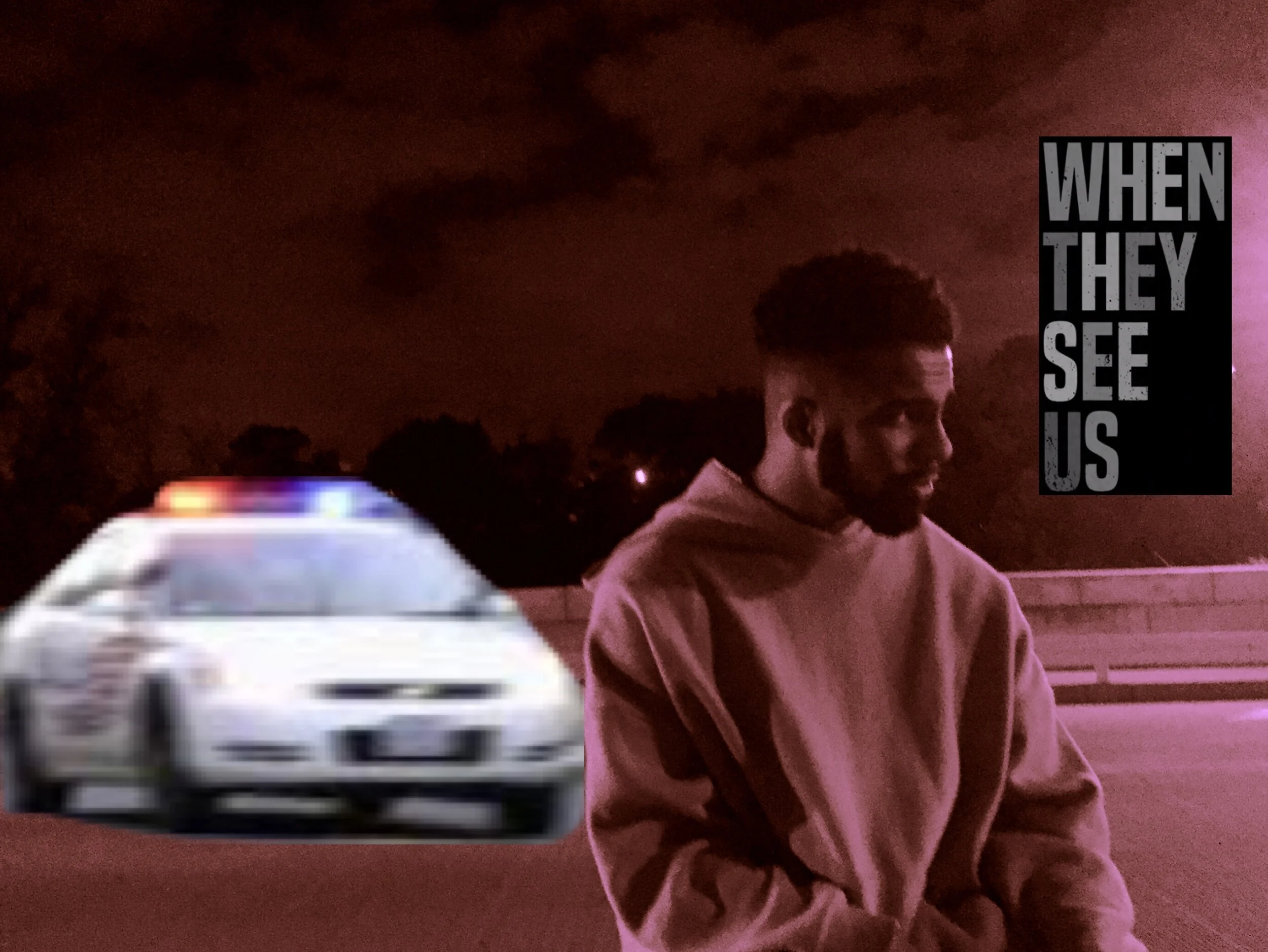

When They See Us, a Netflix mini-series chronicling the untold story of the “Central Park Five,” brings to light the egregious and brutal human rights violations the boys faced at the hands of law enforcement.

The audacious work by producer-director Ava Duvernay is a gutting reminder of the horrors the boys endured. According to their testimonies, their names and home addresses were leaked to the public despite them being underage. NYPD detectives physically abused the boys, which led to the now-infamous coerced video confessions that were used as evidence during the trial. Of all the haphazard evidence presented by the prosecution — led by Elizabeth Lederer, who up until this summer was an esteemed professor at my university’s law school — the only thing that made these boys targets was that they were Black and Latinx without wealth. They lacked access to the types of protections white boys are afforded, even if such white boys are found guilty of heinous crimes.

In When They See Us, Duvernay captures the humanity of five boys of color viciously robbed of their childhoods. In America, Black youth are not imagined as children and DuVernay poignantly shows us the consequences of that truth.

However, the most resonant scenes in the series are not the heated back-and-forth arguments between attorneys in the courtroom or upsetting details of the investigation. They are the moments when the boys are captured sharing tenderness. In one scene, Yusef Salaam (Ethan Herisse) laughs and jokes with his friends as his dark brown skin glows underneath the city street lights. In another, Antron “Tron” McCray (Caleel Harris) appears talking about Yankees players with his father while eating a bowl of cereal in the morning.

This is what we need — more depictions of Black youth simply existing in the world — because in the United States, Black youth are criminalized for their existence. DuVernay reveals how something as mundane as childhood is a luxury for many Black and brown boys and girls that can have it snatched away at any moment.

My experience watching this mini-series as a Black boy only a few years older than some of the “Central Park Five” when they were first imprisoned was deeply upsetting to say the least. I see myself in the characters. It was a painful realization that the only thing separating me from being in their shoes is sheer luck and circumstance. Our paths are close, so close that I walk the same campus as the prosecutor responsible for destroying their lives.

It is not enough to have freed the “Central Park Five.” It is not enough to apologize. It is not enough to expect an apology from one of the people responsible for spawning the media spectacle that called for their deaths, even if that person is now the racist sitting president. It is not enough to have paid them $41 million dollars in damages. Antron McCray, Kevin Richardson, Yusef Salaam, Raymond Santana, and Korey Wise had their life trajectories altered and that cannot be erased. No amount of money or apologies can replace the time they so unjustly lost.

It is clear the anti-Black criminal justice systems in place in this country that made these wrongful convictions possible must be abolished and reimagined. But we must also ensure that young Black people are not caged in the public imagination before they are caged in prison cells. We deserve to be free, to be ourselves, to exist. If substantial change does not occur, we should all prepare to watch the same mini-series all over again, real soon.